It’s that time in an election … when party leaders are asked (usually by journalists) (assuming they’re allowed to ask questions) about when voters can expect to see the party platforms.

As someone who has been tasked with helping to write a couple of them (2015, 2019), I have to wonder … does anyone actually care? Like, really? Other than me?

My gut says that having access to a complete and costed party platform probably doesn’t move a lot of votes, and research seems to back this up. From a September 2021 report by Narrative Research:

When asked what is most important when choosing how to vote in a federal elections, one-third of residents reveal they typically vote for the same party every election. Meanwhile, a similar proportion of Canadians indicate they vote based on the policy or issue positions of the parties and two in ten vote based on the leader of the party. Fewer than one in ten Canadians indicate that they decide based on the local candidate or another reason.

Still, I think platforms serve an important — arguably, essential — accountability function. What did the parties say they were going to do? When and how were they going to do it? And what was it supposed to cost? If you care about democracy (and gosh, I hope you do), you should care about political parties’ willingness to be held to account for the promises they make in an effort to secure your support. (That said, absolutely zero shade from me if you’ve never actually read a platform. We try, but they’re not exactly designed to be a scintillating read. I’m happy if you take even just a few minutes to look at a platform aggregator like this or this or this).

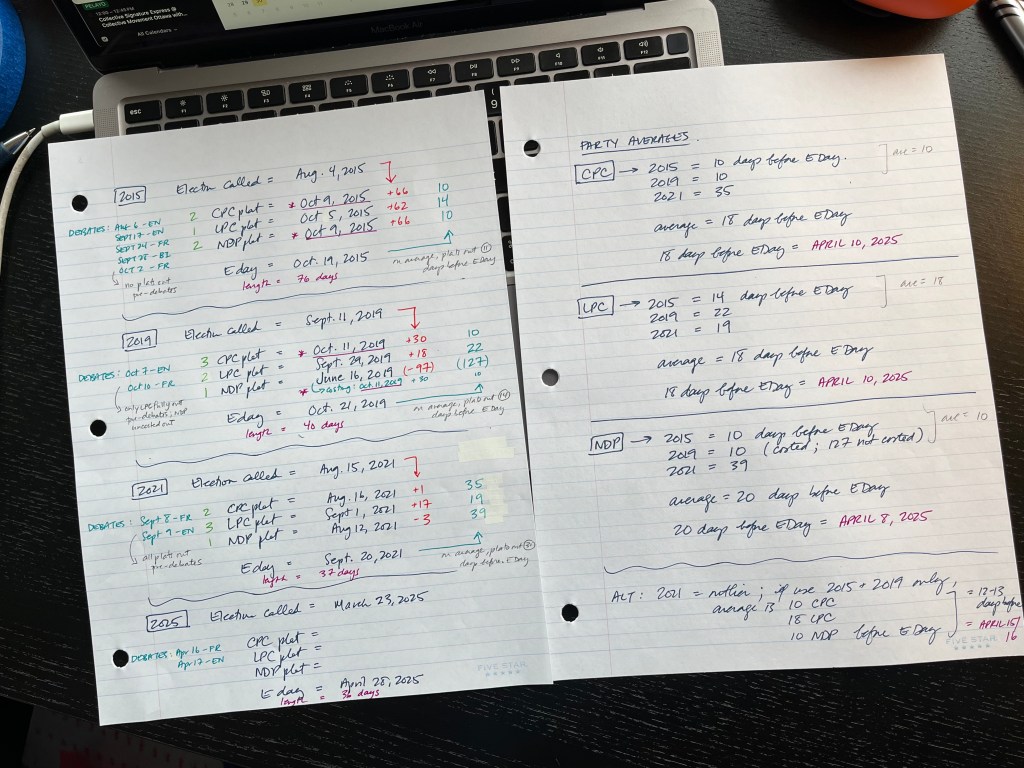

Because I’m curious about when we can expect to see platforms from Canada’s three main parties — none of which have released platforms yet, and we’re past this election’s halfway point — I decided to crunch some numbers and found some interesting results. Short version is that if we look at past practice in the last three federal elections, all three parties are late … but not if you ignore the 2021 data, which was a bit of an outlier.

My main findings …

- 2015 was the only recent election where no parties had their platforms out before the leaders’ debates (that year there were five debates; the last one was on Oct. 2 and party platforms were released on Oct. 5 (Liberal Party of Canada) and Oct. 9 (Conservative Party of Canada and New Democratic Party)

- In 2019, only LPC had a costed platform out before the leaders’ debates (NDP‘s platform was out, but uncosted)

- In 2021, all parties were able to release platforms ahead of the leaders’ debates (that year, LPC was last to release)

- There were a few times where parties were very early with their platform releases; this includes the 2019 election (NDP had their uncosted platform out 97 days (!) before the election was called) and the 2021 election (CPC released their platform on the first full day of the election (which blew my mind more than a little bit))

- On average, in 2015, parties had their platforms out 11 days before election day … that grew to 14 days before election day in 2019, and to a rather shocking 31 days in 2021 (that much larger number was aided by the fact that in 2021, the NDP released their platform three days before the election was called, with CPC following just a few days later)

Looking at each party separately …

- CPC historically releases its platform 18 days before election day … if that trend had continued to 2025, we’d have expected to see their platform released yesterday (April 10, 2025)

- LPC follows the same trend at 18 days, meaning that we’d have expected to see their platform yesterday, too (April 10, 2025)

- NDP tends to release their platform a bit earlier, on average, 20 days before election day … that means we’d have expected to see their platform at the beginning of this week (April 8, 2025)

As noted above, though, 2021 was a bit of an outlier, with two of the three main party platforms released early on; if we drop 2021 from the data and just look at how things were done in 2015 and 2019, I think we get more “typical” timeframes. Looking at just 2015 and 2019 data …

- CPC and NDP released their platforms 10 days before election day, which means we’d expect to see their platforms late next week (April 18, 2025, after the leaders’ debates)

- LPC remains unchanged even if we drop the 2021 data; we’d expect to see their platform by now (April 10, 2025)

One last way of looking at the data is to average out all three parties, to land at a kind of “ideal launch date” that’s informed by when all three parties have released platforms in the past … if you look only at the 2015 and 2019 data and assume 10 days before election day for the CPC and the NDP, plus 18 days before election day for the LPC, that gives an average release date of 12.5 days before election day, which would be mid-week next week (April 15 or 16, 2025).

Phewf! That’s a lot of info, I know. What do I think will actually happen this time around? My best guess — 100% based and gut and 0% influenced by any insider knowledge (which I do not possess) — is that we’ll see at least two of the three parties release their platforms before next week’s leaders debates. Probably one on Sunday and one on Monday. But that’s just a guess!

What are my sources for this data?

Roughly speaking, the internet. Mostly news stories and reaction pieces, with any vague dates (“last Tuesday …”) cross-referenced against the calendar. If any of my students are reading this, no, “the internet” is not an acceptable source, and yes, you’ll get dinged marks for trying.

What kind of platforms are we talking about?

Generally speaking, I mean the “main platforms” that the political parties release during an election campaign that include all of their commitments along with estimated costs. “All of their commitments” is meaningful because sometimes parties will release major planks in the months leading up to an election (LPC did this with their environment / climate plan in 2015) and “with estimated costs” is also significant because I don’t think parties give voters the full picture unless/until they provide costing. In recent years, costing has sometimes included a review of the numbers by the Parliamentary Budget Office (interestingly, this was a 2015 LPC campaign commitment!). I’m not a numbers person, and I can’t speak meaningfully about this process, but you can read what my colleague Dr. Jennifer Robson (and my partner Dr. Mark Jarvis) had to say about the international experience with public costing of party platforms. I’ll note that 2019, the NDP effectively released two separate platforms; in June — fully three months before the election was called — they released what I’ll call their “ideas book,” followed by a costed document 10 days out from the election (I’ve used that latter date in my calculations, in an attempt at apples-to-apricots comparisons).

Can we see your notes?

Sure, why not. There’s nothing magical about them (except, perhaps, the skill needed to decipher my handwriting).

Why’d you only look at the three main parties? What about the Greens, the Bloc, the PPC?

Because I’m doing this for fun. It’s not a formal research project, it’s already taken a couple of hours to do this much, and I have a pile of grading to finish, sheesh.

Finally, to circle back to this post’s title … where are platforms typically launched?

Typically, platforms are launched at some kind of event; it’s not unusual for platform launch to be the “announcement of the day” during a federal campaign. You’ve seen these before: the party leader standing behind a podium and in front of a wall of supporters, holding aloft a printed version (sometimes spiral bound or stapled, because that’s how close parties can get to not having a printed version ready for the event).

Where do these events happen? Not surprisingly, Ontario was home to the majority (five of nine) platform launches between 2015 and 2021. Quebec got two — both times in Montreal. The only party to venture further afield was the CPC, with platform launches in Surrey (2015), and Delta (2019), British Columbia. The LPC seems to have a particular fondness for Ontario launches; every launch since the turn of the century (furthest back I looked) has been in Ontario.

As a fellow writer of platforms I enjoyed this so much. Nice research!

LikeLike

Thanks! As a person who was always more taken with words than numbers — numbers were Tyler’s job! — I had a lot of fun poking around at this.

LikeLike